A Year Without Summer — Apocalyptic Paintings of the 1815 Mount Tambora Eruption

Erika Fredrickson

March 18, 2018

Courtney Blazon is not the kind of person to idle away an afternoon. The Missoula, Montana-based artist is known regionally for her elaborately colored, often creepy, and extremely surreal marker-and-ink projects, most of which have her working late nights or around the clock. So, in August 2015, when Blazon did finally take a vacation on the banks of the St. Lawrence River, she brought with her six hefty, heady books to keep her busy brain occupied. One of those books was The Year Without Summer: 1816 and the Volcano That Darkened the World and Changed History. The book, by historian William Klingaman and meteorologist Nicholas Klingaman, is about the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora, in what is now Indonesia. The eruption produced a “volcanic winter” in 1816 — a “Year Without Summer” — which had dramatic global effects.

Blazon was inspired. “I had my pen and was making notes in the margins,” she says. “When I first started thinking about what I might do with this story, I wasn’t thinking about it quite so deeply, but then I started to go down a rabbit hole.”

Blazon spent six months researching and developing the project. Besides the Klingamans’ book, she drew on Gillen D’Arcy Wood’s Tambora: The Eruption that Changed the World. In the summer of 2016, exactly 200 years after the Year Without a Summer, Blazon holed up in her studio for three months. (She jokes that 2016 was her year without a summer.) The result was a series called The Year Without Summer. It features four large-scale illustrations and dozens of smaller pieces rendered in extraordinary detail that explore Mount Tambora’s eruption and the eruption’s far-reaching consequences.

The artwork combines environmental history with Blazon’s surreal sensibility. It spans a fantastic stretch of time, and deals in death and illness, folklore, climate change and art. Researchers have explored connections between Mount Tambora’s eruption and subsequent events around the world, making both well-corroborated and more speculative links. Blazon explores the possibilities of these links in her work. “The lines I’m tracing between events are jagged,” she says. In addition to creatively exploring the past, Blazon uses her art to explore the future. “Even though we have so much more knowledge about climate science today,” she says, “we’re all still under this veil of not understanding the larger picture. How is what we’re doing now impacting the future?”

For her work on The Year Without a Summer, Blazon drew from the books by the Klingamans and Wood. Here, we explore the artistic details of the series’ four main pieces, which Blazon created based on the historical facts from those books.

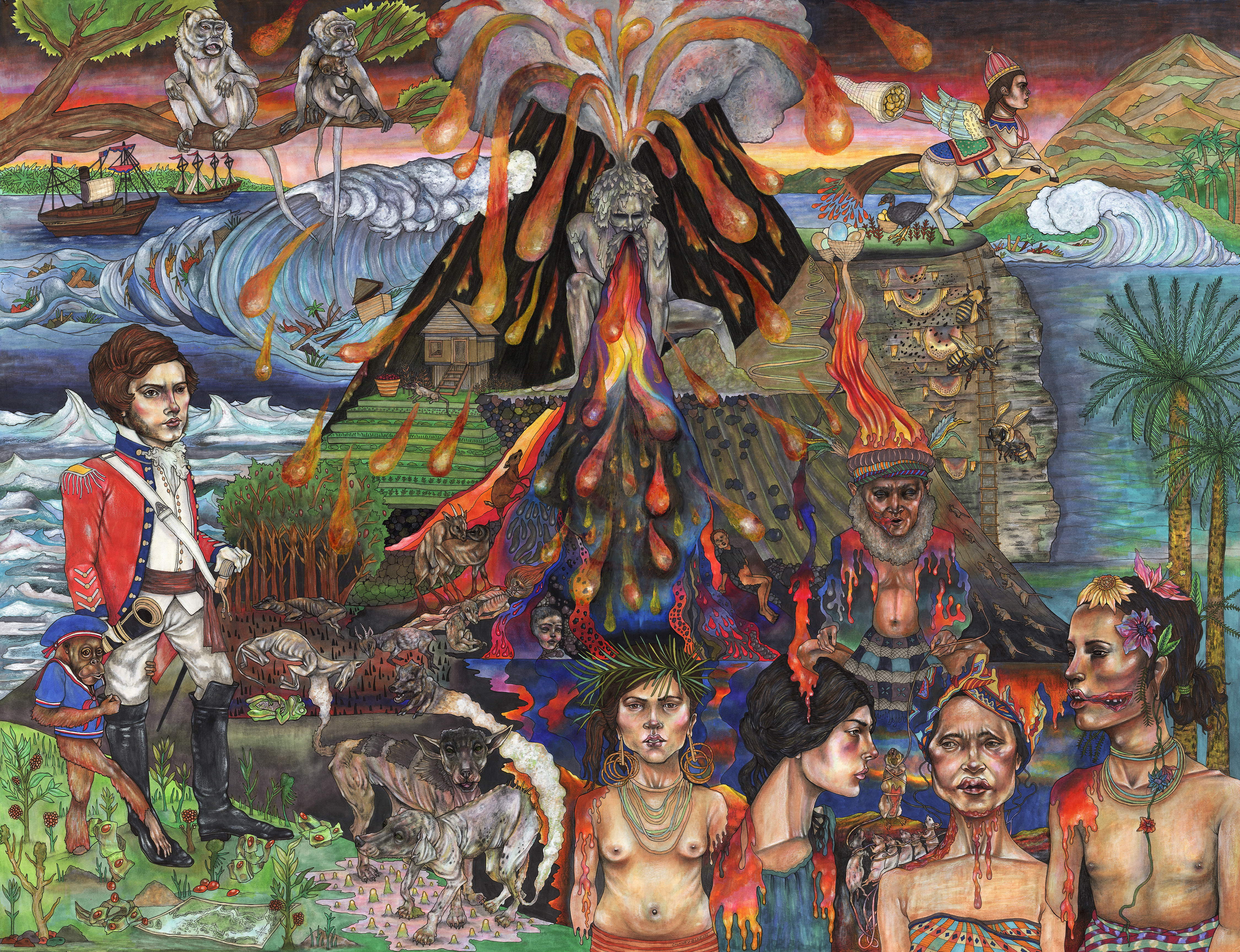

Zaman Hujan Au (Time of the Ash and Rain)

The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora killed tens of thousands of people and decimated a whole ecosystem of wildlife and plants. Very few escaped, and most of those who survived the initial blast slowly died from famine and disease. In The Year Without Summer, the Klingamans wrote: “Over the following month, thousands more perished — some from severe respiratory infections from the ash that remained in the atmosphere in the aftermath of the eruption, others from violent diarrhoeal disease, the result of drinking water contaminated with acidic ash. The same deadly ash poisoned crops, especially the vital rice fields, raising the death toll higher.” In this piece titled Zaman Hujan Au (Time of the Ash and Rain), Blazon depicts the moment of eruption in bright reds, blues, blacks, oranges and yellows. In the bottom right-hand corner, a few inhabitants of the island appear to be dripping in lava and possibly melting away.

Courtney Blazon, Zaman Hujan Au (Time of the Ash and Rain), 2016, pen and marker on paper.

No one knows what the island people would have looked like. The volcano destroyed the civilization, and present-day Indonesians aren’t related to them. The Tambora culture had been heavily influenced by traders from the Netherlands and China, and, with that in mind, Blazon recreated what they might have looked like with the help of an anthropologist at the University of Texas.

In the bottom left-hand corner is Sir Stamford Raffles, the British Governor of Java at the time of the eruption, accompanied by his orangutan whom he dressed in men’s clothes. Raffles was a self-styled naturalist who had been visiting Sumbawa for years collecting specimens from the island’s rich flora and fauna. He was hundreds of miles away when the volcano erupted, but when he realized the extent of the disaster, he sent relief ships. It was mostly too late. Afterward, his catalog of preserved and live specimens offered a glimpse into what the landscape was before Mount Tambora’s eruption. He also documented the strange weather after the eruption.

Above Raffles, in the tree branches, are crab-eating macaques — a notable monkey in the area. In the archipelago of the Indonesian islands where Sumbawa sits is the Wallace Line, named after Alfred Russel Wallace, who was a contemporary of Charles Darwin. (They both would have been children at the time of the eruption.) That line separates the Asian animals from the Australian animals, but the crab-eating macaque is one of the few animals that crosses the line. Their images riff on the mystic monkeys who symbolize “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” and serve as a warning about turning a blind eye in the face of disaster.

At the time of the eruption, Sumbawa people had a strong economy: They were known for their honey, horses, birds nests and sandalwood, among other things. Under Raffles’ feet are sandalwood pods, and if you look closely at the piece you’ll find images of birds nests and bees, as well as other agricultural aspects of their economy.

For months prior to the eruption people on the island had felt rumblings from Mount Tambora. In that time, disasters of any kind were often attributed to the anger of the Gods, and Tambora was no exception. In the picture, an angry god, who appears to be central to the volcano’s activity, crouches in front of Tambora, vomiting lava onto the land. There’s also a fiery man sitting cross-legged, seemingly perched on the island women’s heads. He represents another theory the people of Sumbawa had: That the disconcerting sounds from the volcano’s depths came from a holy man who had the power to reanmiate dead dogs and who, when invoked, caused volcanic activity.

Détails sur Le Fin Du Monde

The change in climate after Mount Tambora produced strange weather in Europe and led to the creation of two beloved monsters. In the summer of 1816, Lord Byron and his personal physician, Dr. John Polidori, rented the Villa Diodati near Lake Geneva and took in several visitors, including Mary Godwin and her lover, Percy Shelley. The incessant rain and wind made it hard to be outside, so the writers holed up in the villa where they told German ghost stories to each other to pass the time. Lord Byron made a game of it, encouraging everyone to make up their own creepy tales. Two of those stories were expanded upon and published later. Polidori’s The Vampyre (which was initially attributed to Lord Byron) is credited with popularizing an early romantic version of the blood-sucking character. Godwin, who would of course become Mary Shelley, published Frankenstein two years later.

Courtney Blazon, Détails sur Le Fin Du Monde, 2016, pen, marker and oil pastel on paper.

Though they wouldn’t have understood the climate science behind the Mount Tambora’s eruption or how it linked to the subsequent cold, dark year they experienced afterward, writers including Lord Byron and Mary Shelley used it as direct and indirect inspiration for their art. In Détails sur Le Fin Du Monde, Blazon drew Lord Byron “shivering on the terrace of the Villa Diodati in front of an icy Lake Geneva.” Here he’s composing his poem “Darkness,” while taking tea with death. “Darkness” was in direct response to the time but also a vision of the apocalypse.

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air.

He continues to describe a landscape of famine and greed and despair, and of the earth he wrote: “Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless.”

Records of the Year Without a Summer are more complete in places like North America and western Europe, while documentation in Australia and Africa are scarce to non-existent. “This piece is like a geographical portrait of the summer of 1816 that can be read from right to left, east to west, across Indonesia, China, India, Switzerland, Sweden, Germany, Italy, England, Ireland and America,” Blazon says. New Englanders referred to the year 1816 as “eighteen-hundred-and-froze-to-death.” On the far right, Blazon has drawn Thomas Jefferson sitting in front of Monticello holding a rain gauge. Jefferson’s love for recording weather helped document the extreme cold New England was facing. This was also a time when Jefferson went into debt over crop failures that appeared to be directly related to the unusual cold.

Other places also experienced unusual cold and crop failures. In between Jefferson and the Villa Diodati you can see barren agricultural land illustrating widespread famine, which became most prevalent a few years after the eruption. In Germany, for instance, the year 1817 was knowns The Year of the Beggar. Blazon represents famine in both realistic and fantastical ways. On the left side of the piece, halfway up, is a pony rearing with leaves falling out of its stomach. Famine forced some people to eat anything, even their favorite ponies (Sumbawa had been known for breeding ponies). They also sometimes mashed up dead leaves to create a paste for sustenance. The image combines these two things.

Above the pony is a depiction of the southwest province of Yunnan, where floods and frost destroyed rice crops and farmers turned to opium for their new livelihood, helping set the stage for the mid-nineteenth century Opium Wars. These connections are indirect and uncertain, Blazon notes, but they show how a disaster can lead to problems and decisions that might not have arisen otherwise.

Those who were able to escape famine dealt with the climate’s consequences in various ways. Besides the writers, artist William Turner used the dramatic sunsets, caused by ash and dust, as inspiration for landscape paintings. Sunsets fill the top of this picture, and in the upper righthand corner, an image of someone simulating a volcano — representing showmen who used the science of volcanoes to recreate eruptions for entertainment. Another notable aspect represented in the drawing is the worldwide reporting of the weather phenomena “St. Elmo’s Fire” — a blue or violet glow that emanated from spires, chimneys and other pointed structures.

One of the most significant aspects of this piece is Blazon’s depiction of cholera. The patches of colorful bacterium (which latches onto plankton) can be seen at the bottom of the piece almost bubbling up from the earth in the water supply. Despite what they depict — disease and death — the bacteria-infested plankton are eye-catching and fit Blazon’s palette well. “They’re really vibrant and amazing,” she says. “I probably made them a little more poppy than they are, but plankton, in general, are really cool looking.”

The volcano disaster exacerbated many diseases, including typhus, which is carried by lice and swept through the poorest regions of the world. In his book Tambora, Wood writes:

1816 was a time when the overwhelming majority of the world’s population depended on subsistence agriculture, living precariously from harvest to harvest. When the crops failed that year, and again the next, starving rural legions from China to Ireland swarmed out of the countryside to market towns to beg for alms or sell their children in exchange for food. Famine-friendly diseases cholera and typhus stalked the globe from India to Italy, while the price of bread and rice, the world’s staple foods, skyrocketed with no relief in sight.

Unlike typhus, which tended to strike the poorest regions, cholera was an equal opportunity menace. It hit India hard and infected the water supply of entire towns, affecting people across social strata. People burned diseased bodies on funeral pyres or dumped them in rivers, which helped spread the disease. According to D’Arcy Wood, Tambora’s sulfate dust disrupted monsoons in South Asia for three consecutive years, which allowed cholera in Bengal (where it was endemic) to mutate and spread across Asia and, eventually, into Europe.

The Poetry of the Seven Sorrows

The Poetry of the Seven Sorrows piece centers on a specific event that happened in Paris in 1832, after cholera had reached Northern Europe. Poet and journalist Heinrich Heine witnessed a masquerade ball where suddenly, in the middle of the merriment, a harlequin performer fell ill with cholera. Heine reported: “[The harlequin] felt a chill in his legs, took off his mask, and to the amazement of all revealed a violet-blue face. It was soon discovered that this was no joke; the laughter died, and several wagon loads were driven directly from the ball to the Hotel-Dieu, the main hospital, where they arrived in their gaudy fancy dress and promptly died, too … Those dead were said to have been buried so fast that not even their checkered fool’s clothes were taken off them; and merrily as they lived they now lie in their graves.”

Courtney Blazon, The Poetry of the Seven Sorrows, 2016, pen, marker and wax crayon on paper.

The number “seven” refers to a few things: For the purpose of the drawing, Blazon created seven harlequins, all dancing with death (the skeletons). But the meaning of The Seven Sorrows refers to a genre of writing revived by poet Li Yuyang, who witnessed the famine in China after Tambora erupted and the rice crops failed. The Poetry of the Seven Sorrows represents all five sense, plus bitterness and injustice. Yuyang’s poetry was created as a way to bear witness to the atrocious suffering and the atrocities of a local government that failed to help its people.

Grain tax! the policemen shout. Their whips

Slice the air, and the agony of the people

is never ending. Who can plug heaven with a stone,

or command the Shang-yang stop flying?

If only the sun would rise where it should,

And the dragon with his dark clouds disappear.

O our free hearts then! But when I ask if tomorrow

will be fine, the flower under my feet says nothing.

The piece also illustrates events that happened more in the decades after the 1832 cholera outbreak. The poor conditions in New England motivated people to migrate west, pushing out Indians and slaughtering those who resisted. In the upper lefthand corner are images of colonization and genocide.

There were a few less horrific outcomes that happened in the years after Tambora. Hunger spurred invention: The slaughter of horses for food in Europe, for instance, led to Karl Drais developing a prototype of a bicycle, which is illustrated in the upper righthand corner. And environmental disaster also spurred new scientific ideas: The volcanic winter created rapid glaciation in the Swiss Alps, which stimulated scientists, such as Ignaz Venetz, to develop theories about climate change and the role of glaciers in shaping the earth.

Welcome to the Pleasure Dome

The writers and artists inspired by the Year Without a Summer couldn’t have understood how their work would resonate in the future. But their work has resonated, above all, Shelley’s Frankenstein, which generation after generation has returned to for its timeless cautionary tale. This last piece, Blazon takes the voices and themes of the past and lets them reverberate into the future. It’s the piece that, more than any of the others, allows Blazon to become – like the artists she depicts – a commentator.

Courtney Blazon, Welcome to the Pleasure Dome, 2016, pen, marker and pastel on paper.

The title of the piece, Welcome to the Pleasure Dome, is from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s 1816 poem “Kubla Khan,” about the fraught relationship between humans and nature. In the piece, Blazon depicts seven figures – this time, the seven deadly sins, not the seven sorrows. The figures are futuristic, but some of their characteristics allude to the historical depictions of the Year Without Summer. Sloth overdoses on synthetic opiates —a reference to China turning to opium production in the mid-1800s, but also a reference to current issues with opiates. Greed riffs on the motif of Frankenstein and a pile of dollar bills, aka “Benjamins.” (There’s a small image of Benjamin Franklin in Détails sur Le Fin Du Monde.) Wrath wears the latest cholera-inspired designs. The outlier is Pride, depicted by two children. One of the children has her head turned all the way around symbolizing perhaps the only glimmer of hope in this picture: evolution and innovation. “As a country we’re overly prideful, but as individuals we suffer from so many neuroses,” Blazon says. “Maybe we should have more pride in who we are.”

In the bottom left-hand corner, starving polar bears navigate the melting ice cap and albatrosses feast on plastic garbage. At the bottom center of the picture there’s a Ken doll, who represents the fate of Sumbawa, which has become overrun with wealthy surfers and garbage. As if it were an episode of “Black Mirror,” cameras record everything and display it for everyone to see.

There are seemingly endless details here — as in all her works — but Blazon brings it full circle with the image of an airplane seeding the clouds. It’s a manmade attempt to cool the earth in the face of global warming, by replicating the effects of Mount Tambora’s eruption so many years ago.

View Courtney Blazon’s other drawings, including more related to the Mount Tambora eruption, at www.courtneyblazon.com.

Erika Fredrickson is the co-editor of Enviro-History. She received an M.S. in Environmental Studies at the University of Montana in 2009. Since 2008, she’s worked as the arts editor at the Missoula Independent — Montana’s only alt-weekly — where she covers the arts, food policy, and local characters. @efredmt on Twitter.

Citation

Erika Fredrickson, "A Year Without Summer — Apocalyptic Paintings of the 1815 Mount Tambora Eruption," Enviro-History.com, March 18, 2018, http://Enviro-History.com/year-without-summer.html.